Our public programme provides opportunities for engagement, analysis, and reflection on the Råängen programme. It includes events and school workshops, as well as a series of commissioned texts and films. These activities are designed to attract both local and international audiences, to expand the conversation beyond the project in Lund, and to position the programme within a broader critical framework.

Sign up to our newsletter to be kept up to date with future events.

Events

Our programme of events is open to everyone and includes walks, talks, symposia, performances, themed meals, screenings and workshops. Speakers and participants include artists, architects, curators, developers, archaeologists, dancers, and writers.

DIG, SPLASH, DIG! 7 MAY 2022

We worked with Byggstudio, a Norwegian-Swedish design studio, on a programme of events and activities that took place in ‘Hage’ throughout 2022 and 2023.

The theme for the programme was PLAY & RESEARCH and involved local community groups, schools, and residents. Together, we tested ideas and developed networks for long-term partnerships in Råängen.

We held the first event in May 2022 when we invited children and adults to dig mud pits, make earth mounds, learn about the soil in Råängen, and make clay objects with ceramicist Pernilla Norman.

Working With Nothing, 18 jan 2022

For our first online event ‘Working with Nothing – Artists and Architects Building a New Neighbourhood’, we invited the artist and architects who are involved in our commissions programme to talk about the strange, very particular character of the Råängen programme. We were joined by a large, international audience made up of architects, artists, curators, urban design specialists, and writers.

Joining us from Barcelona, Glasgow, Trondheim and Stockholm, the speakers discussed the following questions:

– How can artists and architects respond to a place that doesn’t yet exist?

– How does it feel to work without a brief?

– Does it matter that we are all from elsewhere?

Speakers:

Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores, Flores & Prats Architects

Nathan Coley, artist

Geir Brendeland, Brendeland & Kristoffersen Arkitekter

Chair: Kieran Long, Director, ArkDes

A garden for everyone, 5 Sept 2019

This event at Skissernas Museum in Lund focused on ‘Hage’, Brendeland & Kristoffersen’s public garden for Råängen. Geir Brendeland introduced the practice’s approach to the commission, the design concept, and its relation to Lund. Other Råängen team members discussed elements of the build, the materials, and the connection to theology and community. The evening ended with a lively discussion with audience members.

The event was organised around a long table which echoed the design of the communal table at ‘Hage’. A selection of items connected to the design and construction of the garden were displayed on the table, including watercolours by Geir Brendeland, plans, maquettes, fruit, planning documents, engineering drawings, photos, models, Cor-ten steel samples and bricks.

Read moreIntervene/Shift/Compel, 28 Feb 2019

Our seminar ‘Intervene/Shift/Compel’ was held on 28 February 2019 at Moderna Museet Malmö. Using a prompt from artist Stephen Willats, “What I want to do is intervene in the fabric of society”, we invited five artists and curators from Sweden, Norway and Britain to address the following questions: How can artists contribute to a discussion about the way we live in the 21st century? What are the mechanisms that artists, curators and commissioners use to make democratic, active public spaces that address urgent, political and social issues? Can such projects bring about societal change or shifts in perception?

This event was part of the public programme for Nathan Coley’s Råängen sculpture ‘And We Are Everywhere’. The work addressed questions regarding access to land, homeless states and the role of the church in contemporary life. The aim was to inform the role that art and culture will play in the Cathedral’s long-term urban development programme.

Speakers:

Kerstin Bergendal, artist and Senior Lecturer, Valand Academy, Göteborg

Nathan Coley, artist

Emma Ribbing, artist and choreographer

Eleanor Pinfield, Director, Art on the Underground

Lena Sjöstrand, Chaplain, Lund Cathedral and Co-Director, Råängen

Apolonija Šušteršič, artist

Chair: Jes Fernie, Råängen Curator

Who is everywhere? 16 Nov 2018

For this public debate, Chaplain Lena Sjöstrand invited Lund resident and high profile activist Johan Wester to discuss the questions that have arisen around Nathan Coley’s sculpture ‘And We Are Everywhere’. The artwork has initiated a lively debate in the media and social forums which will be fed into our plans for the Råängen.

Pilgrimage, 12 Oct 2018

This was a wonderful opportunity to walk from the town centre to Råängen to see Nathan Coley’s sculpture ’And We Are Everywhere’, and to discuss the Råängen programme with strangers, friends, and family members. The pilgrimage was led by Magnus Malmgren, the pilgrim priest at Lund Cathedral, with Lena Sjöstrand, Chaplain of the Cathedral/Co-director of Råängen.

Nothing is ever finished, 18 April 2018

For our first seminar, we invited speakers from Lund, New York, Berlin and London to consider the subject of time as a cultural construct and tool for project development. The theme linked to Lund Cathedral’s presence in the town over a 900 year period (since 1123, when the east-alter in the crypt was consecrated) and the commitment to their land in Brunnshög a thousand years into the future.

We discussed the characteristics of long-term projects; the concept of earthly and heavenly time; our fragile relationship to the land; and the varying and magical ways that contemporary artists have worked with the subject of time. We challenged the idea that the future is the only place available for imaginative play; we located Råängen within the history of mankind, and considered pre-modern concepts of time as place.

Speakers:

Cathy Haynes, writer, curator and artist

Anna Lagergren, archeologist

Fiona Raby (Dunne & Raby), academic, architect and designer

Lisa Rosendahl, independent curator

Lena Sjöstrand, Chaplain, Lund Cathedral

Chair: Jes Fernie, Råängen Curator

What is heaven? 27 Jan 2018

We were delighted with the response to our first public debate held on 27 January 2018 at the Domkyrkoforum in Lund. The subject under discussion was Nathan Coley’s artwork ‘Heaven Is A Place Where Nothing Ever Happens’, located adjacent to Lund Cathedral between Nov 2017 and March 2018. The work was a huge talking point in the town; became the focus of many social media posts and lit up a part of Krafts Torg throughout the dark winter months.

Read moreSchools

Involving children in the Råängen programme is one of our key objectives – to encourage young people to talk about the development of their town, what art can do to the spirit of a place, and what home means to them. We’d also like to amass a list of priorities for children in new developments, to ensure that their voices are heard throughout the design stages. To this end, we are working with schools and arts organisations in Lund to deliver a programme of workshops and trips for children, both at primary and secondary level.

HAGE SCHOOLS PROGRAMME

As part of their public programme for Hage, Byggstudio worked with children from Solbjers pre-school and Östratorns primary school to devise a series of clay channels and water pools, guided by ceramicist Pernilla Norrman.

More details on this programme can be found here

And We Are Everywhere schools programme

In October 2018 staff at Lund Cathedral and the Skissernas Museum worked together to develop a programme of workshops and site visits to discuss Nathan Coley’s artwork ‘And We Are Everywhere’.

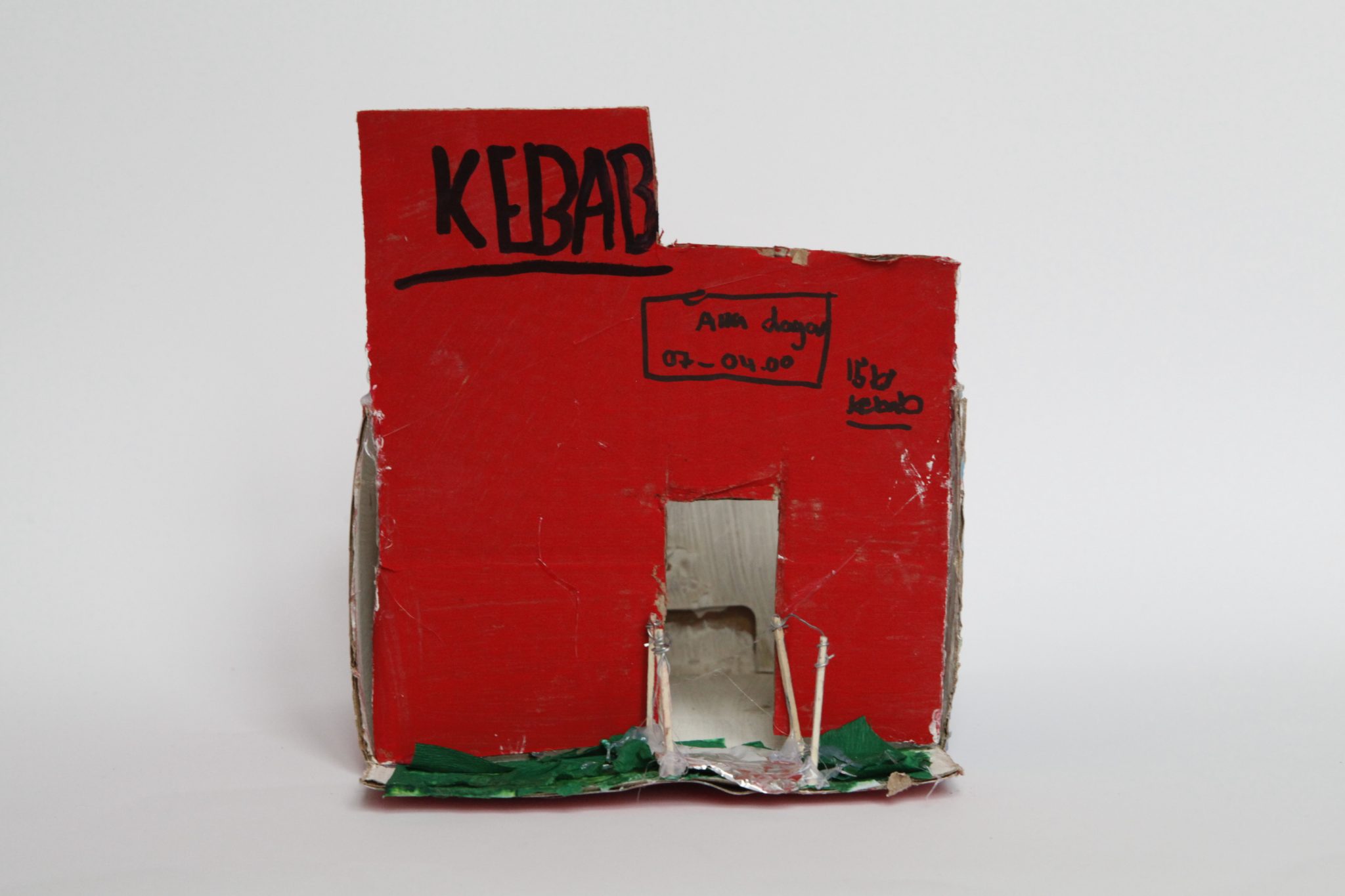

Children from pre-school age to secondary school took part. Day 1 entailed a visit to Brunnshög with a priest and a teacher where children explored issues raised in the work. Students talked about what was important to consider when building a new neighbourhood; what do citizens need in order to thrive?; what is the function of art and how should a city of the future look? For day 2 of the programme, children visited the Skissernas Museum where they saw other examples of site-specific artworks. They discussed the importance of public engagement and participation, continued their conversation about building new towns, and made models of an imaginary new neighbourhood.

These models were on display at the Domkyrkoforum in Lund from 9 Jan – 22 February 2019.

Texts

An important part of Råängen is to reflect on the various themes raised throughout the programme. Here you will find commissioned texts by curators and writers who have been involved in our project. We’ll bring all of these texts together to form a book in future years.

Gillian Darley: Land in Common

Gillian Darley has written a text on ‘Hage’, our public garden for Råängen, which explores the history of shared, open spaces and common ground in India, Scandinavia, Iran, and the UK.

Read it here.

Cathy Haynes: Heaven is in the east

Cathy Haynes has written at text based on a time walk through Lund Cathedral with the Chaplain, Lena Sjöstrand. The event was part of the Råängen Time seminar held in April 2018.

Jonatan Habib Engqvist: Blessed are the meek

Jonatan Habib Engqvist has written a text reflecting on Nathan Coley’s Råängen commission ‘And We Are Everywhere’ (2018–2019).

Films

Due to the incremental and open-ended nature of Råängen, we are commissioning short films to document specific points in the process, disseminate the programme more widely, and to capture some of the multiple voices involved. Films made to date include interviews with artists, Lund Cathedral clergy, curators, architects and local residents.

October 2019

Hage is a public garden in Råängen which opened in 2021. This film captures various moments through its development and includes interviews with the architect Geir Brendeland, Råängen Co-Directors Lena Sjöstrand and Mats Persson, as well Jake Ford from White Arkitekter, and the fabricators at Proswede.

July 2018

‘And We Are Everywhere’ was a new commission by Nathan Coley for Råängen, located on the Cathedral’s land in Brunnshög from June 2018 to March 2019. In this film the Bishop of Lund, Johan Tyrberg, responds to the work; artist Nathan Coley, curator Jes Fernie, and landscape architect Jake Ford discuss the issues raised through the work.

February 2018

‘Heaven Is A Place Where Nothing Ever Happens’ by Nathan Coley was installed adjacent to Lund Cathedral from November 2017 to March 2018. In this film Co-Director of Råängen and Chaplain of Lund Cathedral, Lena Sjöstrand, talks about the work with curator Jes Fernie, and members of the public respond to the work.