(Den här artikeln finns endast på engelska.)

Cathy Haynes explores Lund Cathedral with its Chaplain, Lena Sjöstrand.

This article is based on a public conversation between its author Cathy Haynes and Chaplain Lena Sjöstrand as they toured Lund Cathedral in April 2018. The event was part of the Råängen seminar, ’Nothing is Ever Finished’, which took the theme of time to begin a discussion about the Church’s new development on the outskirts of Lund, to be built between 2020 and 2050.1Råängen was established in 2017. www.raangen.se

Picture yourself talking to someone about the future and gesturing towards it. Which way do you point?

Chances are, if you’re in the contemporary West, you’d motion straight ahead or to the right as if following a line of text on a page. Your own internal sense of time might differ from that, but it’s probably what you and your audience would understand in common. If you were speaking Mandarin, though, you’d most likely point downwards. An ancient Hebrew person would gesture backwards. For Kuuk Thaayorre speakers in Australia, the order of events runs east to west, no matter which way you personally happen to be facing.

Simply put, while we may differ culturally and personally in how we think of time, nonetheless we tend to imagine it in form of space, often organised around our body. Given that, how are actual architectural environments designed to express different ideas about time? And shape our bodily sense of it?

In the secular West, we talk about time as if it’s the same thing in every home, car, shop and office across the cosmos – running everywhere to the beat of universal standard time. It’s as if there’s only one kind of time, with no outside and no internal quality of difference. But the idea of time being the same everywhere is historically new and culturally specific.2In scientific terms, it’s also a PAST theory. In the 20th century quantum physics proved how, at an atomic level, time runs faster for an object the closer it is to a field of gravity, such as that belonging to the Earth. Hence the physicist’s witticism: your face is older than your feet. And it can mask, I think, the variety of environments of time in our midst, with temples being a special example.

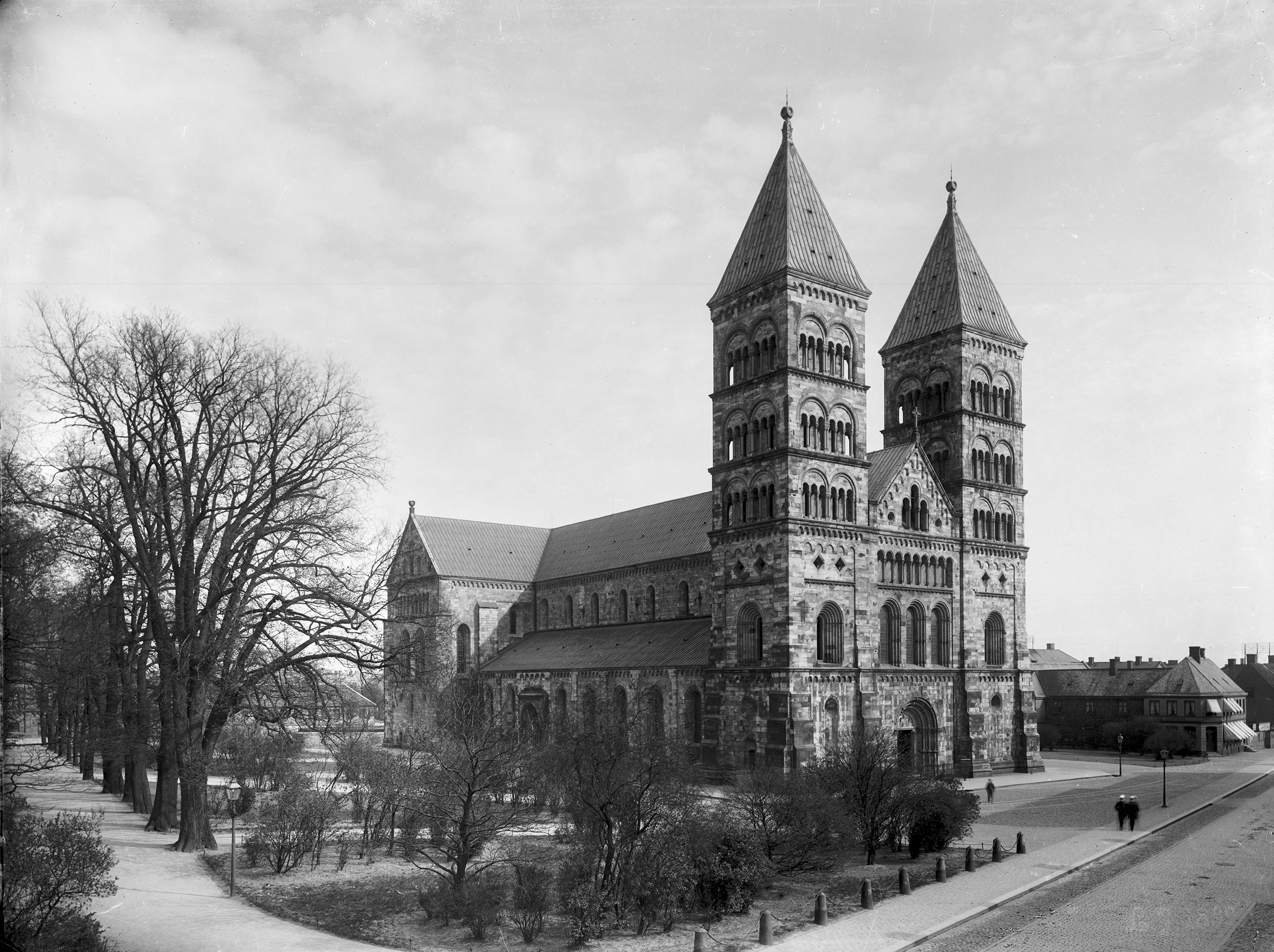

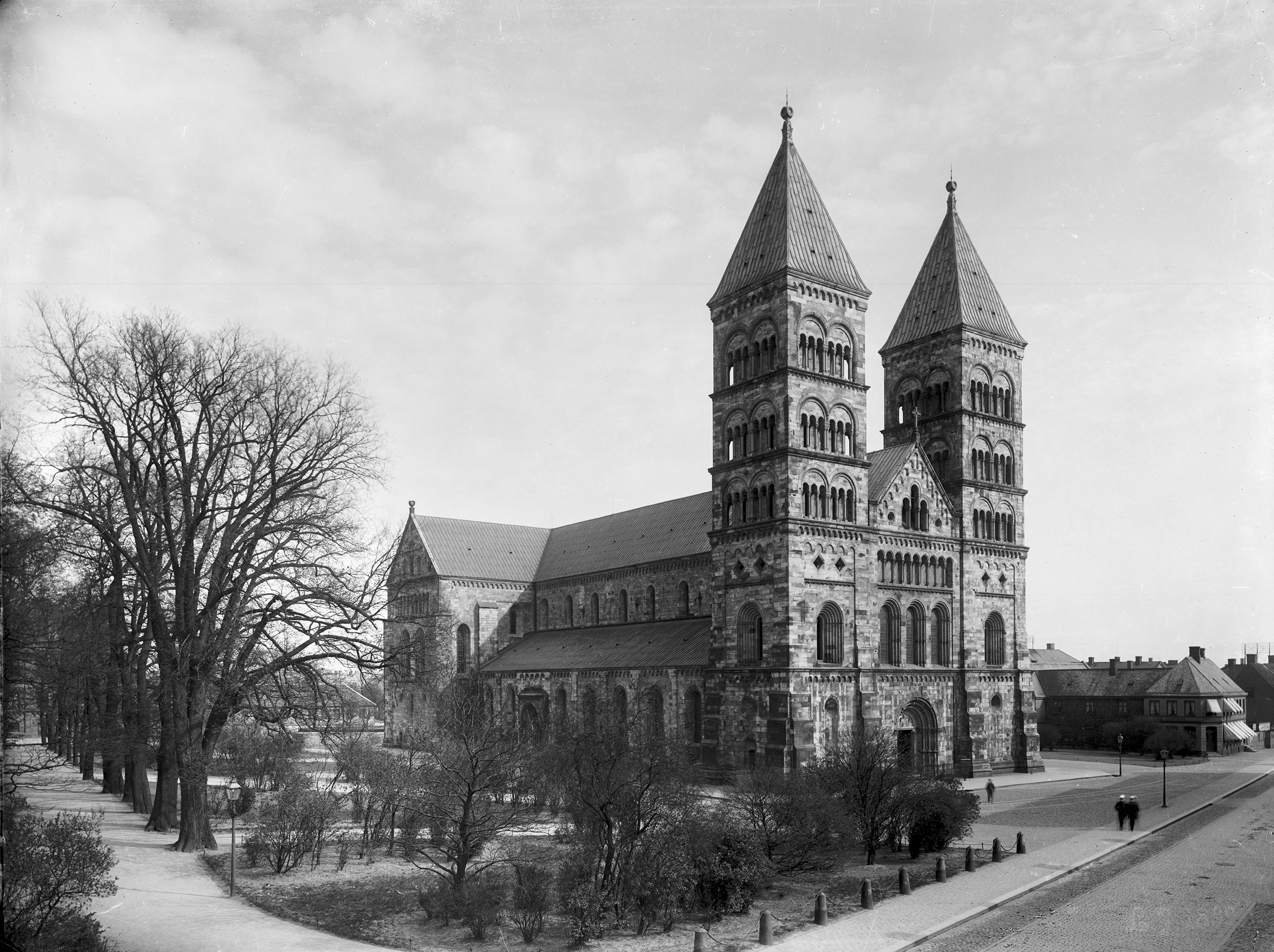

Inside sacred spaces, time often has a more complex structure, form, variety and rhythm than the standard tick-tock or the straight line of progress. As we’re going to explore here, that isn’t just true for traditions that developed outside Christian Europe. With the generous guidance of its Chaplain, Lena Sjöstrand, this essay takes a tour through Sweden’s oldest church, Lund Cathedral3The Cathedral in Lund was consecrated in the early 12th century, with its oldest elements dating to the 1120s. It was then Roman Catholic, and now Lutheran Church of Sweden. – an extraordinary exception to the mainstream notion that time flows the same everywhere.

Lund Cathedral, showing the main entrance in the west wall. Per Bagge 1899. Historical Museum at Lund University.

Crossing the threshold

When you step inside Lund Cathedral, you come to a place where ‘time is special’, says Sjöstrand, smiling warmly.

She ushers us through the entrance vestibule tucked inside the west wall and I look up with a sense of release and awe at the huge high-vaulted space on the other side. This main part of the Church interior is called the ‘nave’, thought to be from the Latin for ship. I brush my fingers over stone worn smooth by two-dozen generations of other hands, and it does feel as if we’ve come aboard a kind of sandstone ark, a sanctuary carrying precious things over the sea of ages.

But tangible, touchable ‘pastness’ isn’t the only special quality of time that Sjöstrand means. Rather, she suggests, as we walk deeper into the Church, we’re going to move through different states of profane and sacred time.

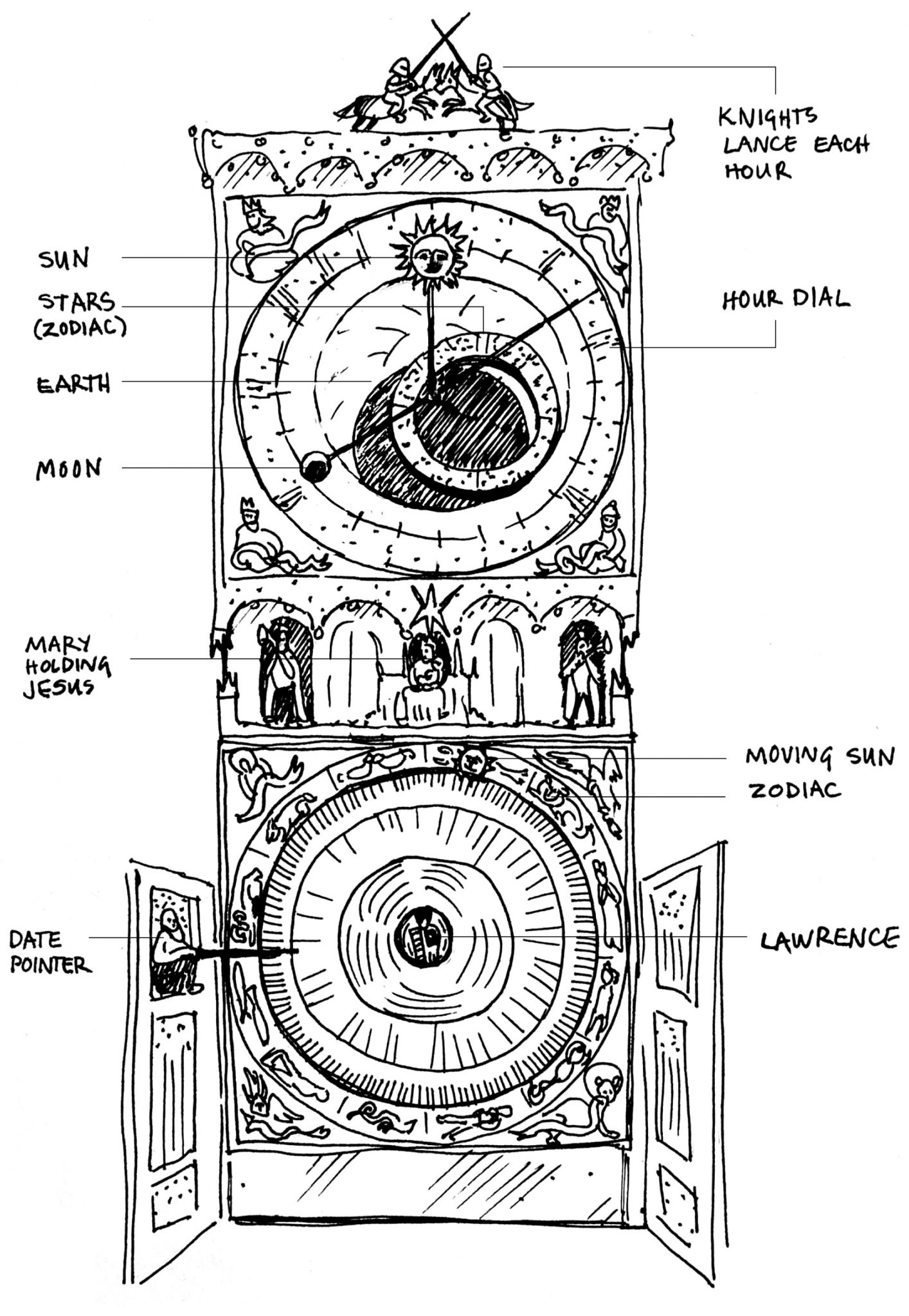

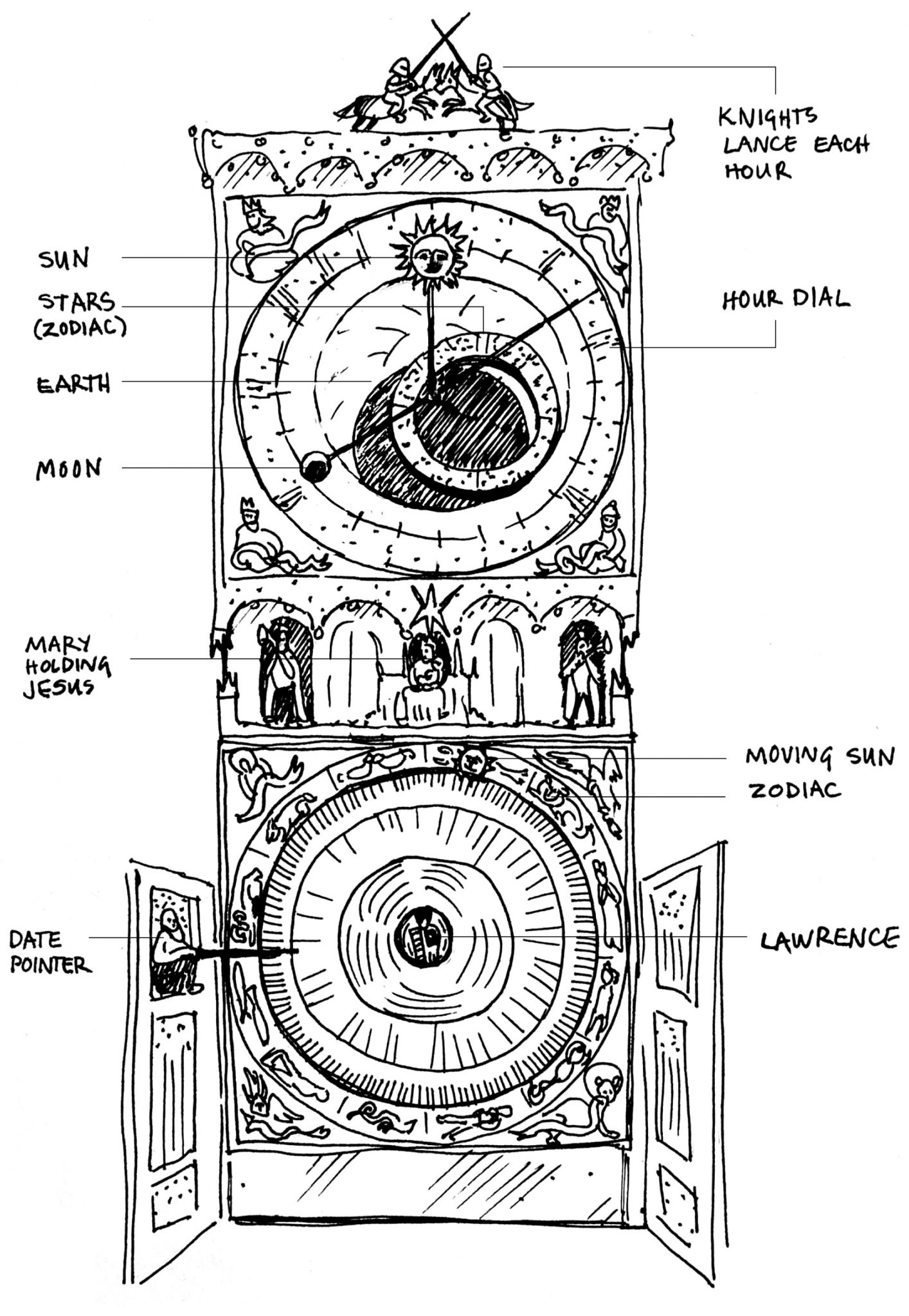

Lund Cathedral clocktower. Drawing: Cathy Haynes.

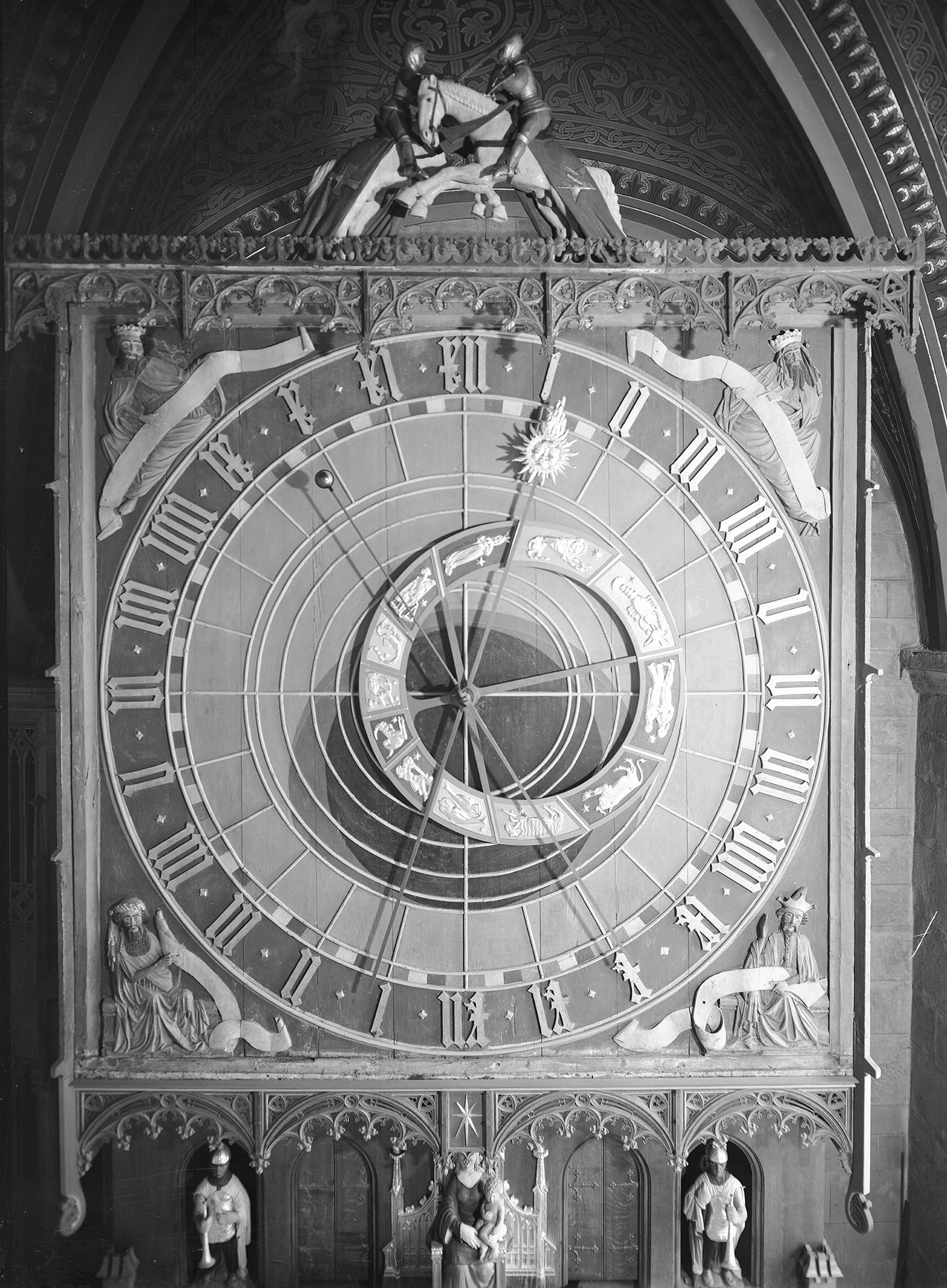

The astronomical clock

We head left from the nave to the north aisle to look at the world-famous early 15th-century astronomical clock. From a distance, I see it’s a tall painted wooden tower with two large discs on the front, like the eyes of a giant head on its side.

The blank white lower disc is mysterious. Up close it turns out to be a set of papery wheels within wheels covered in neatly hand-written notes. These rotate at different rates, marvellously combining to give the sacred dates and phases for each calendar year over 200 years to 2123.4 Why does the Cathedral need this device? Many events in its sacred calendar happen on the same date each year. But some, like the Passion, Holy Week and Easter, appear to drift against the backdrop of the solar year because they’re timed by the Moon not the Sun. The calendar wheel is an ingenious mechanism for reckoning both kinds of date, while giving a far longer perspective on time than our usual year-long calendars.

The upper disc is more familiar – at first glance it’s easy to imagine it’s just a beta version of the classic modern clockface because of its hour hand and dial. But that’s arguably the limit of its exact match with our way of counting time.

When you peer at the dial more intently, what appears to be the second hand is in fact a moon hand. This is ferrying a spinning black and white ball to show the phase and place of the actual lunar orb in the sky right now.

There’s also a golden ring, patterned with zodiac symbols, slowly circling the dial. This signals roughly where we’d find the major star constellations if we could see through the roof and clouds above us, and shows where the Sun and Moon are moving among them. The hour hand carries the gleaming face of the Sun on its tip and, likewise, this isn’t solely an ornament. Because the dial is marked with twenty-four rather than twelve hours, the little golden disc takes one solar day (rather than half a day) to get back to the same point. That means it, too, is tracking its own fiery referent across the celestial vault: when the Sun is highest above us around midday, the hour hand points straight up; when the Sun is lowest beneath us at midnight, it points straight down.

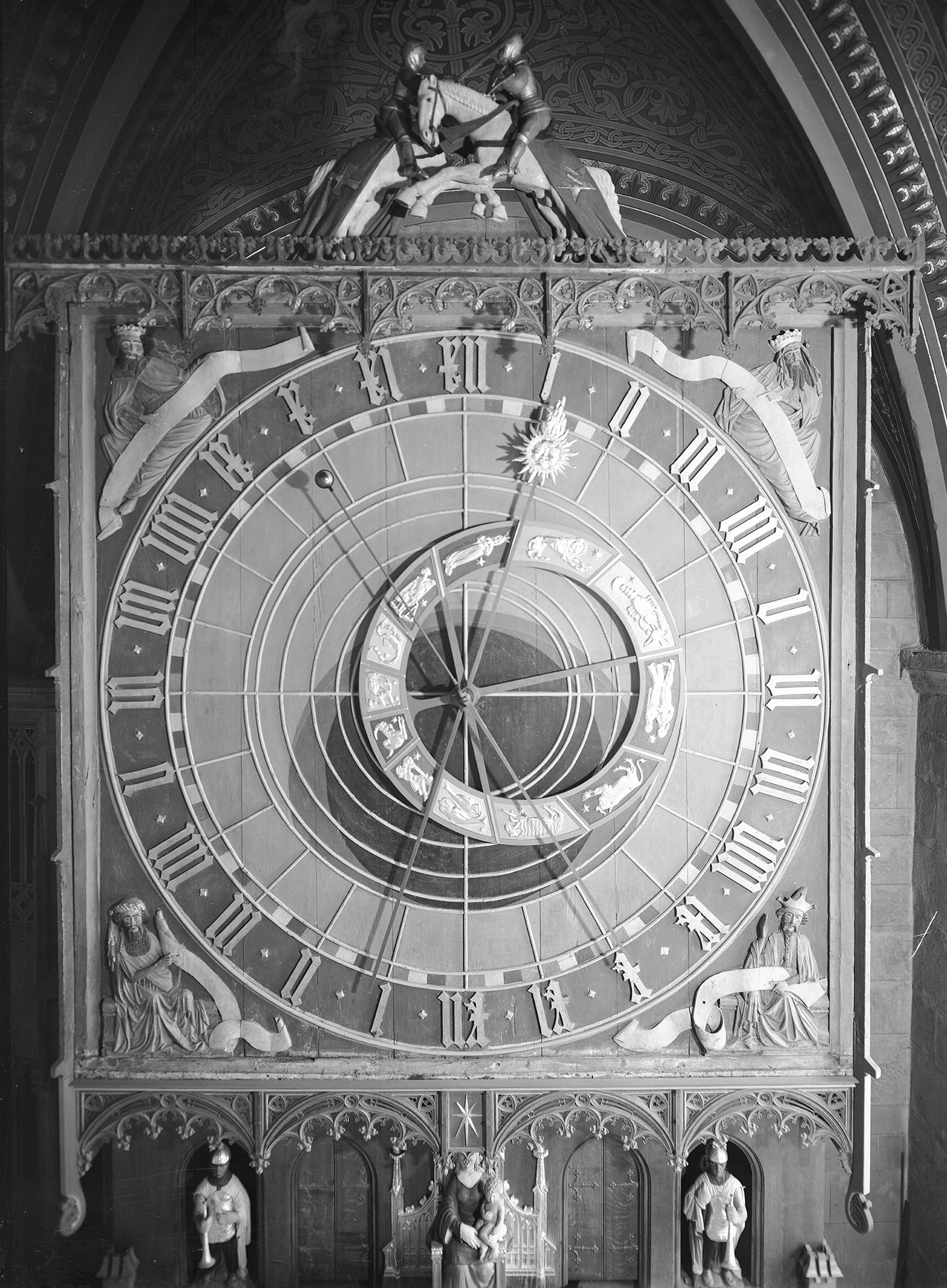

The upper half of the clocktower, showing the astronomical clockface. Photo: Theodor Wåhlin, 1923. Historical Museum at Lund University.

There’s much more to the clock’s ingenious system of signs. But these three things already show how, while it may lack the quantitative dicing of our timekeepers,5The smallest unit on the Cathedral clock dial is the band of little coloured chequers marking the quarter-hours, to which the hour hand gestures as it passes. it far outdoes them with its glorious cornucopia of different kinds and measures of time.

The culture that produced it told time directly, bodily, by observing myriad clues and tools: the shortening of shadows, the transit of Venus, the colour of the sky, the migration of swifts, the ripening of berries, the rhythm of a song, the lowering of a candle. From that sensibility, time is made from the fluxing matter of life. Time has – is – sound, colour, texture, temperature, scent, taste. It’s not a spectral digit dolled out by machine.

We might assume early clockwork timepieces automatically sounded the death knell for a multi-sensory understanding of time – replacing personal know-how, detaching time from living processes, reducing its rhythm to a mechanical monotony. But perhaps that shift isn’t an inevitable function of clockwork, because this timekeeper seems thoroughly embedded in telling the hour by concrete things. Its face is no less than a moving picture of the solar system – not an abstract map of metrical units.

At its heart is a black disc, representing the Earth, sitting inside a blue disc, as if we’re looking at the horizon silhouetted against the sky. In other words, the clock pictures the Earth – or rather Lund – at the centre of the Universe, not the Sun. It’s astronomically false, for sure. Yet it’s faithful to what appears to be happening in the celestial sphere when viewed from this point on the planet, right here and now. It’s a guide to what we could actually see for ourselves if sky conditions were right.

For Sjöstrand, the picture it gives of personal orientation resonates more broadly with how we navigate the world:

I think it’s very touching that the clock measures everything from Lund – Lund as the centre of the world! We think of the Universe from the point where we are in our bodies and in our lives, and react from that place. Sometimes that’s good, sometimes not. But the Cathedral clock is organised by that principle.

I glance down briefly at the clock icon on my smartphone. It’s a skeuomorph, a thing that mimics the material form of something else, like photo-print flooring that gives the ersatz feel of ‘real wood’. In this case, it’s a digital number-counter designed to look like a clock face made of hard three-dimensional matter. It strikes me that the clock face is a kind of skeuomorph too, at least in the sense that it’s a model of the Universe with the hour hand like a solidified sunbeam circling a mechanical Earth. That would make the tiny timepiece on my screen a skeuomorph of a skeuomorph – doubly abstracted from its source.

We forget the clock face was once a moving picture of Sun and Earth. Yet that idea is still there in the design of the clock symbol on my screen if I want to look for it.

God the Clockmaker

From a medieval Christian point of view, God is the Great Clockmaker and the cosmos is His celestial machine.6Thanks to Anita Larsson for first pointing this out to me. This clocktower, Sjöstrand explains, is a working model of that holy scheme.

It has two halves. The clock disc represents Heaven and the calendar disc is the Earth. Both run to divine plan. But each has a fundamentally different temporal constitution: the upper part is eternal; the lower is the world of time.

That division is easier to grasp, I think, if you recall the biblical idea that Adam and Eve fell from God’s immortal realm into mortality, into time itself. We, their earthly children, experience past, present and future. Yet for omniscient God, all time is one.

Today our clock doesn’t seem to refer to anything outside itself other than the abstract, empty count of standard time – 12pm, say, is a convenient multi-purpose measure precisely because for us it has no intrinsic meaning.

Yet for the medieval thinker, God’s eternal clock – made of Sun, Moon and stars – directs earthly time and fills each hour with a special quality. The accuracy of a clock like this is tested by how faithful it is to what’s happening in the celestial canopy. Its reference is outside itself. The Universe is its measure, not the other way round. And so it really matters where the moving pieces on its face point as the day turns.

Now the Chaplain mentions something about this clock I hadn’t noticed: its timing is off by an hour. That’s because Lund Cathedral time has stayed loyal to the Sun. What do I mean by that? Let me explain with a little history.

Around a century and a half ago, clocks were generally set by local noon, by when the Sun is highest above you. In effect every place had its own tiny time zone because solar noon, say, in Stockholm is about 20 minutes earlier than in Lund. The complexity of every town down the line having its own time caused chaos for the new railway networks. To meet such pressures in the Age of Speed, time was officially delinked from the Sun and attached to the standard clock, synched to the mechanical heartbeat of the body politic. Noon no longer meant the apex of the solar arc – the moment the hour hand appears magnetically pulled upwards by the Sun at its highest. When ‘railway time’ began taking over clocks, wrote Charles Dickens in the 1840s, it was ‘as if the sun itself had given in’.

Today the Cathedral horologe keeps standard central European time for most of the year. But, crucially, it doesn’t change for ‘daylight saving’ in summer. The hour hand hasn’t leapt ahead, the Chaplain explains, because the actual solar orb hasn’t jumped across the sky. Its little golden disc is still tethered to the Sun, if more elastically than before.

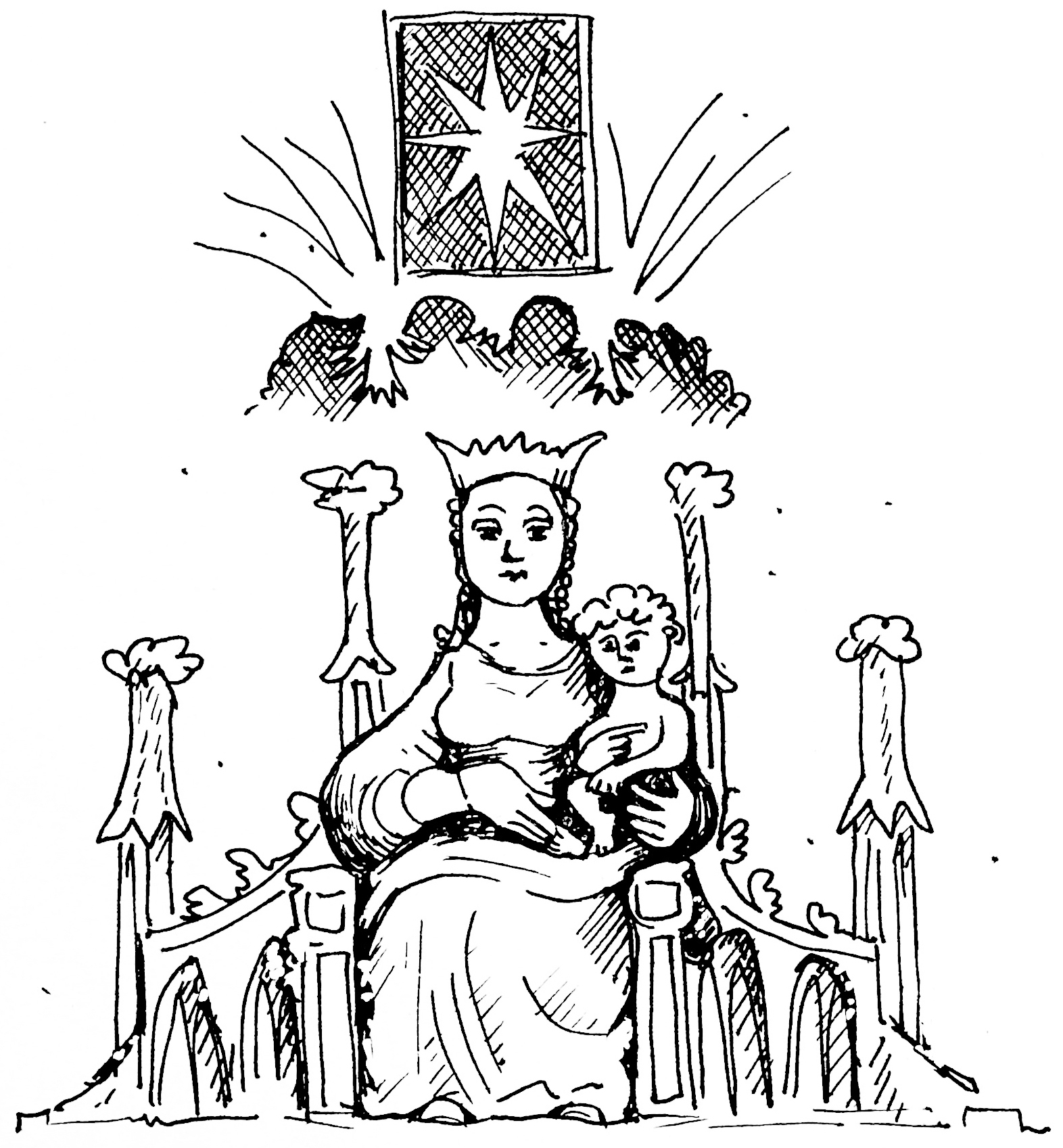

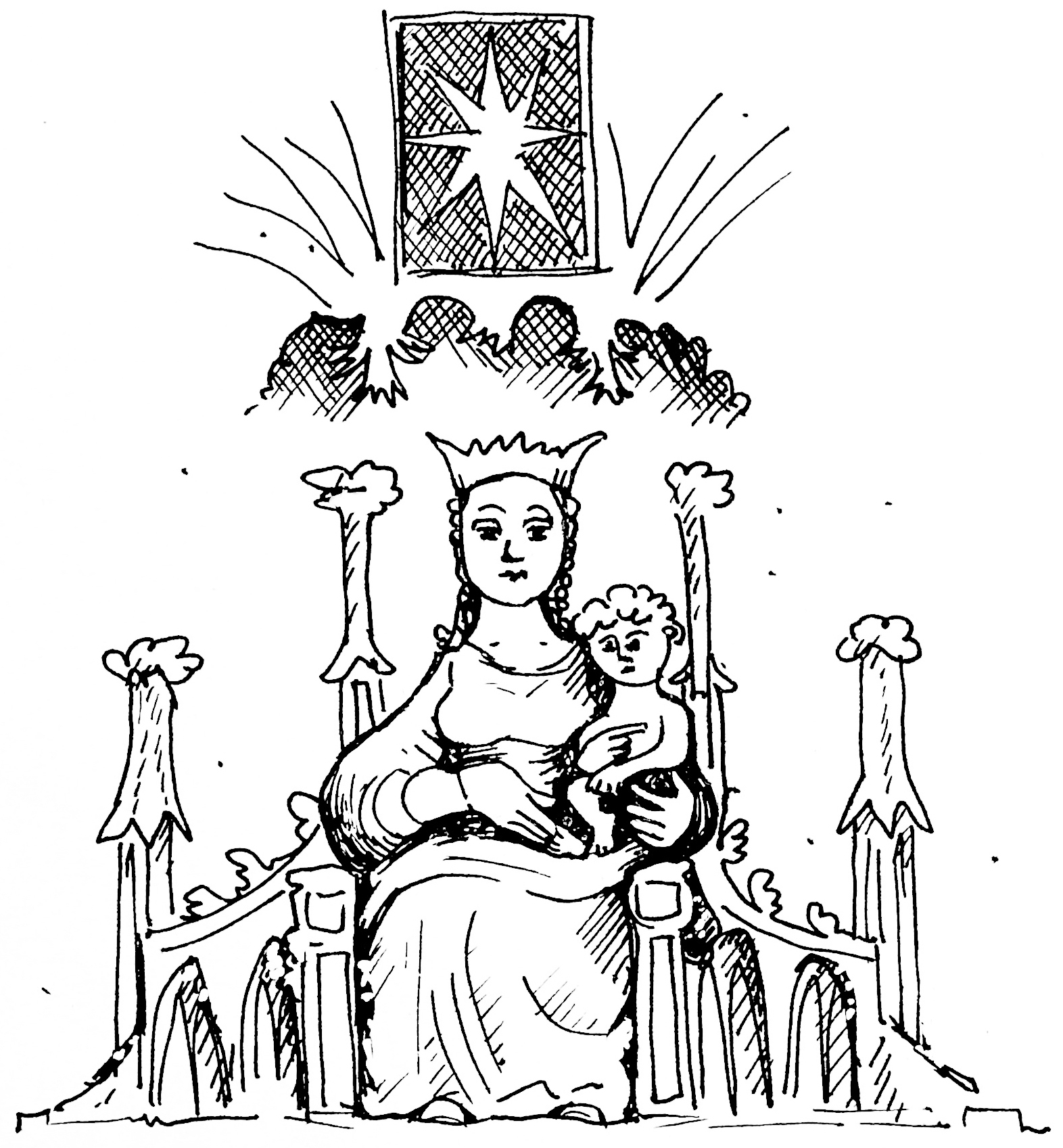

The Holy Family at the middle of the clocktower. These figures on the middle and lower part of the clock were created by the artist Anders Olsson when the clock was restored in the 1920s. Drawing by Haynes of Olsson’s artwork.

The Holy Family

Between the two main halves of the clock is a slim middle section. At its centre sits a rather resigned-looking Holy Virgin holding the baby Jesus in her lap.

The Chaplain explains that, in the clock’s symbolic scheme, these human manifestations of the Holy Spirit are the mediators between Heaven and Earth.

A couple of guards stand either side of Mary and Jesus. Twice a day they raise their trumpets in salute. Then the clock’s miniature organ starts up and a little procession led by the holy kings of the world comes out to parade past and bow to the divine family.

The performance happens twice a day. The first is at midday, arguably the most important hour on this clockface.7The second procession is at 3pm every day. The timing of the first procession changes on Sunday when it moves from noon to one pm.

Noon

At noon, the ancients believed, the Sun casts no shadows. Nature pauses. Change is suspended. Imperfection, signalled by the presence of shadows, is overcome. And time is charged with rapturous, transcendent potential.

Christ, the Light of the World, is profoundly associated with the Sun. And from a Christian viewpoint, the Sun’s rise each day resonates with the Messiah’s ascent to Heaven. Noon, then, is the peak time of connection between the two dimensions. It’s the temporal equivalent of a cathedral spire piercing the celestial canopy, you could say, opening up a channel to eternity. Or, as Matilde Battistini puts it in her fine book ‘Symbols & Allegories in Art’, midday is ‘the hour of divine inspiration and mystical union in which the full symbolic power of the Christ-Sun becomes manifest’.

On the Cathedral clock, this is when the hour hand holds the golden disc at the pinnacle of a line that runs up from the centre of the calendar wheel through the Holy Family. That heavenly alignment is played out not just in the vertically stacked form of the clock as a whole, but also in the upward-pointing architecture all around us in the Cathedral. It’s also there in its shapes: in the ceiling domes and the rectilinear ground and walls. In classical symbolism, the circle and the square are the elemental forms of Heaven and Earth. So this building seems to match that idea, making it in its own way a model in miniature of the Christian cosmos.

The circle of the year

There’s a tiny old man sitting to the side of the calendar wheel. He’s gesturing with a stick at one of the lines of inky lettering on its surface. He looks like a teacher giving a lesson – or perhaps a fisherman angling for opportunity in the big round pool of the year.

The date pointer at the side of the calendar wheel. He also points perpetually to Saint Lawrence at the wheel's hub. Drawing by Haynes of Olsson’s artwork.

The note he’s pointing at has today’s date, which appears to be a Saint’s Day. That surprises me because this is a Protestant church. The Chaplain clarifies:

We don’t pray to the Saints but we see them as people from whom we can learn something – how to live, and things about faith. They’re part of our tradition and history. We are ‘in family’ with them, so to say. And I think telling their stories is a way of bringing history with us into the future, and not leaving it behind.

The most important saint here is Lawrence, patron of Lund Cathedral and its Diocese. In a sense, he’s the human parent of its trans-historical sacred community.

A carving of Lawrence sits at the centre of the calendar wheel. He looks out at us from the apple of its eye with dignified composure. Oddly he’s holding a gridiron in his hand almost as if to say, ‘See this? You’ll never guess what happened to me the other day.’ I’m startled to learn he’s carrying the vile instrument of his own martyrdom.

Lawrence was an early church deacon in Rome. In 258 CE he was ordered by Emperor Valerian to hand over the church assets to the Imperial Treasury. In response, he gave them to the poor. Then he took a band of the most disadvantaged people to the Prefect and declared them to be the church’s true riches. For such disobedience, the Prefect had him chained to a gridiron and burnt alive over hot coals. The story goes that after he’d suffered greatly, Lawrence called to his torturers and joked, ‘Turn me over! I’m done on this side.’ And that’s how he came to be the patron saint of comedians as well as the poor – like a kind of holy Robin Hood with jokes for arrows.

For Sjöstrand, Lawrence’s story presents a very powerful combination of ideas:

It brings together our responsibility for those in need with the potential of humour to fight back against the abuse of power.

Jokes can be, in her view, both a protective shield and a vehicle for transcendence – a way of piercing the illusion that there’s no alternative to this present reality, of breaking the bubble of ordinary time, of performing your way out of a kind of temporal prison.

It’s striking how central playfulness is to religious practice for Sjöstrand. And time, she says, is a construction that can be played with too, as it is here in this Church.

Saint Lawrence at the middle of the calendar wheel. Drawing by Haynes of Olsson’s artwork.

The calendar of things

‘Now we’ve measured time,’ the Chaplain says, ‘we’re going to turn our back on the clock’ and ‘move from time to eternity as we go deeper into the Church’.

We return to the nave and walk up the building’s keel to its prow. From this point, there are no more clocks to consult. But there are plenty of other signs of time. As we’ve begun to see, every element here is devised and placed to create a finely textured symbolic architecture. And some of its features change form and position over the seasons.

We’re in the Easter period just now. That means the clergy wear white and the Church is dressed with lilies to signify the divine light. The carving of Christ with the legend ‘Feel not worried’ has been moved to its central spot. Similarly the baptismal font is currently in its Easter position in the nave; as we pass, Sjöstrand quietly dips her fingertips in the basin and dots her forehead with holy water.

There are non-visual, non-tactile signs of time too, like the Easter hymn the organist was practicing earlier. And the scent of incense that’s still hanging in the air from last Sunday’s Easter service: its gradual waning over the course of the week, its olfactory rhythm, gives a sense-measure of the days that have passed between Sabbaths.

Together these changing forms, materials, colours, sounds and scents make up a kind of calendar of things played out in the space of the Cathedral. You can feel by your senses what kind of time it is.

Lund Cathedral apse from the outside. From Horace Marryat’s travel memoir, ‘One Year in Sweden; Including a Visit to the Isle of Götland (Vol. I)’. John Murray, London, 1862.

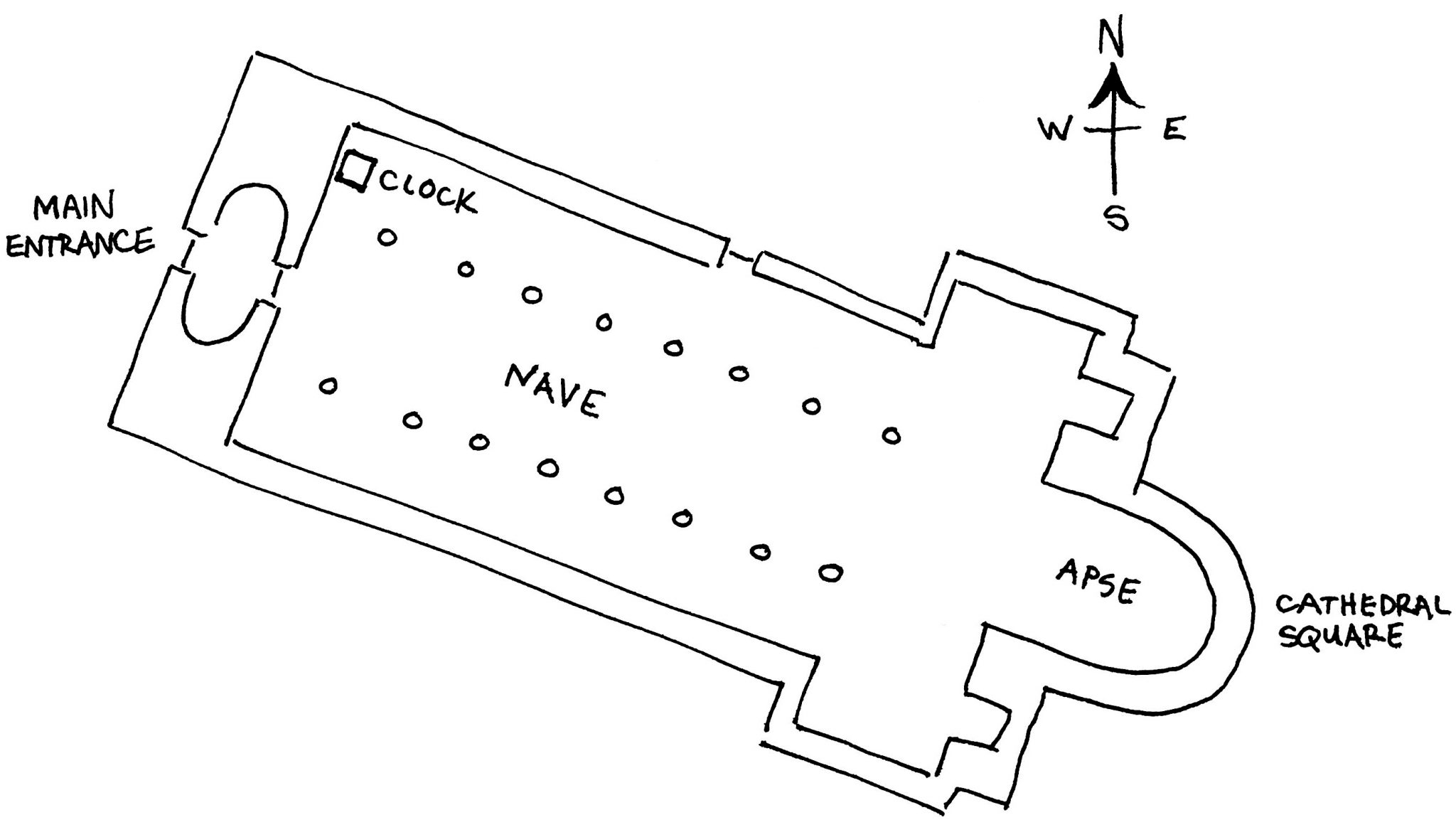

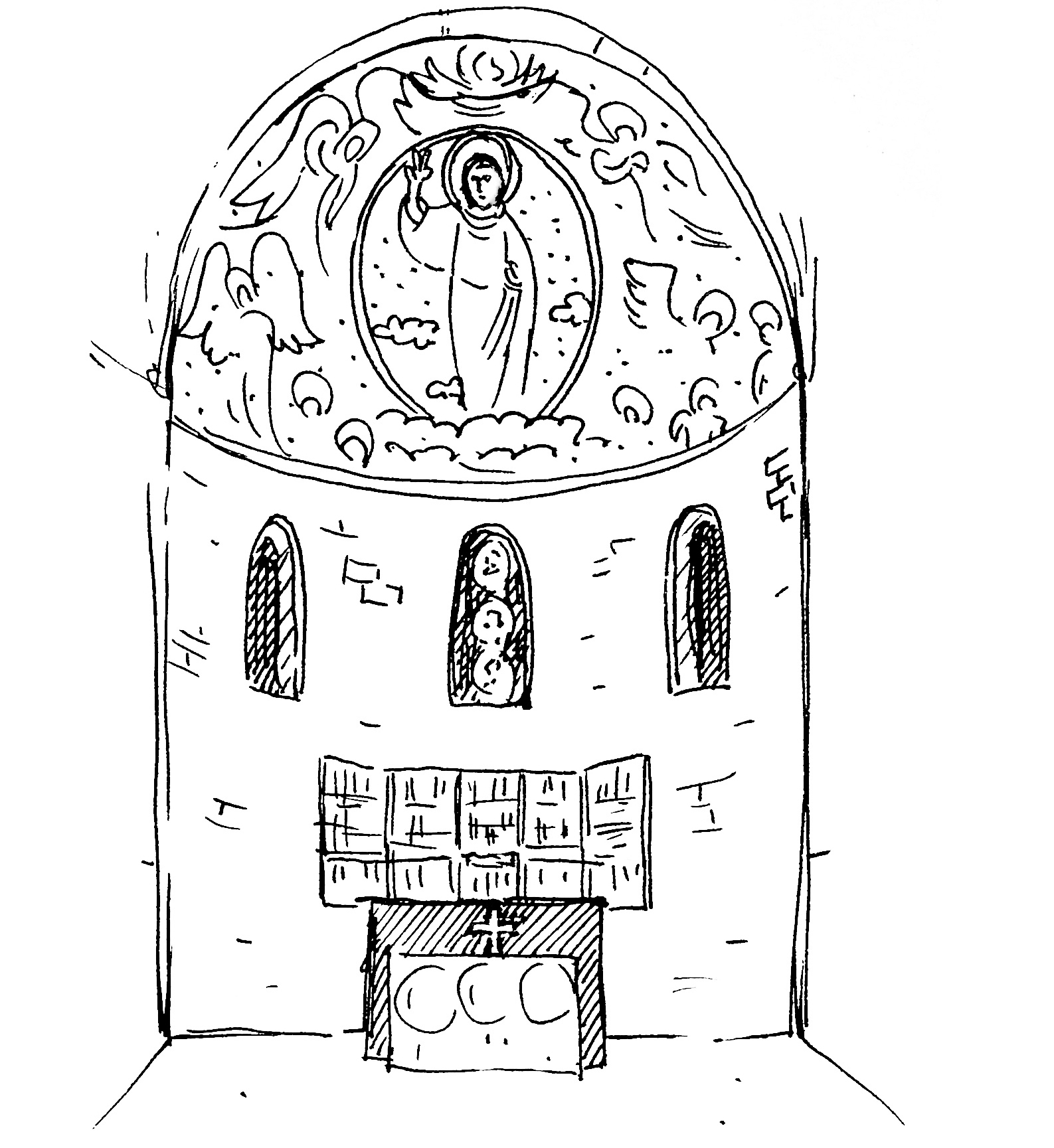

Standing at the edge of time

We’ve climbed the twenty or so steps to the altar and are looking up at the curved wall that shelters the altar like a cupped hand. The space inside the wall is called the apse. We send our imaginations sailing up to see how it sits within the whole.

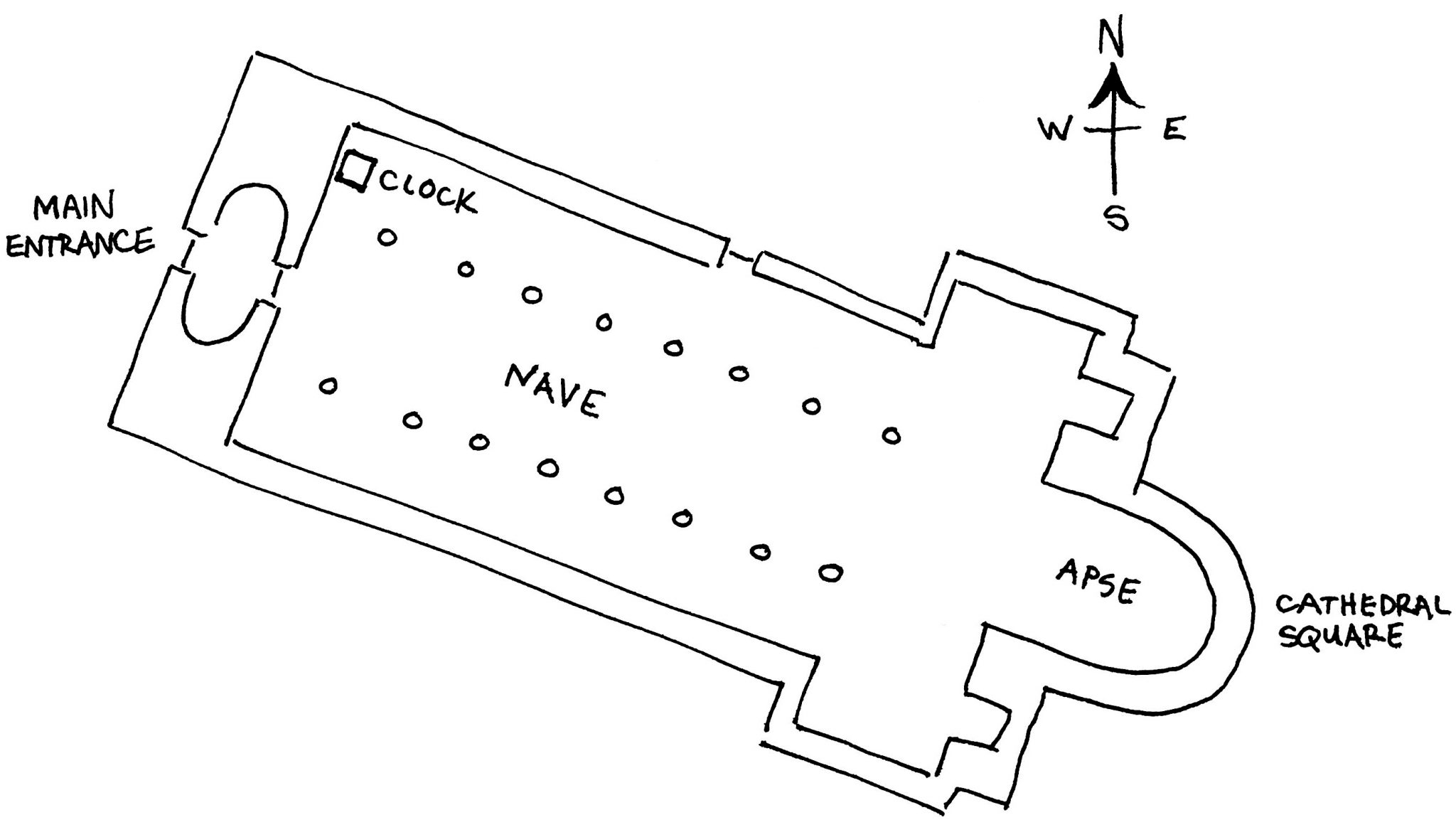

From a god’s-eye view, the Cathedral is laid out like a cross set flat on the ground. The nave is the pillar. The north and south transepts form the crossbar. The apse is the top of the pillar and the building’s main entrance is at the base.

Both entrance and apse are concave while the rest of the Church footprint follows straight lines. It seems that on the earthly (horizontal) dimension, these two places are where the elemental forms of Heaven (the circle) and Earth (the square) join up.

Plan view of Lund Cathedral. Drawing: Cathy Haynes.

If the entrance bubble is the threshold between ordinary and sacred time, what kind of boundary is the apse?

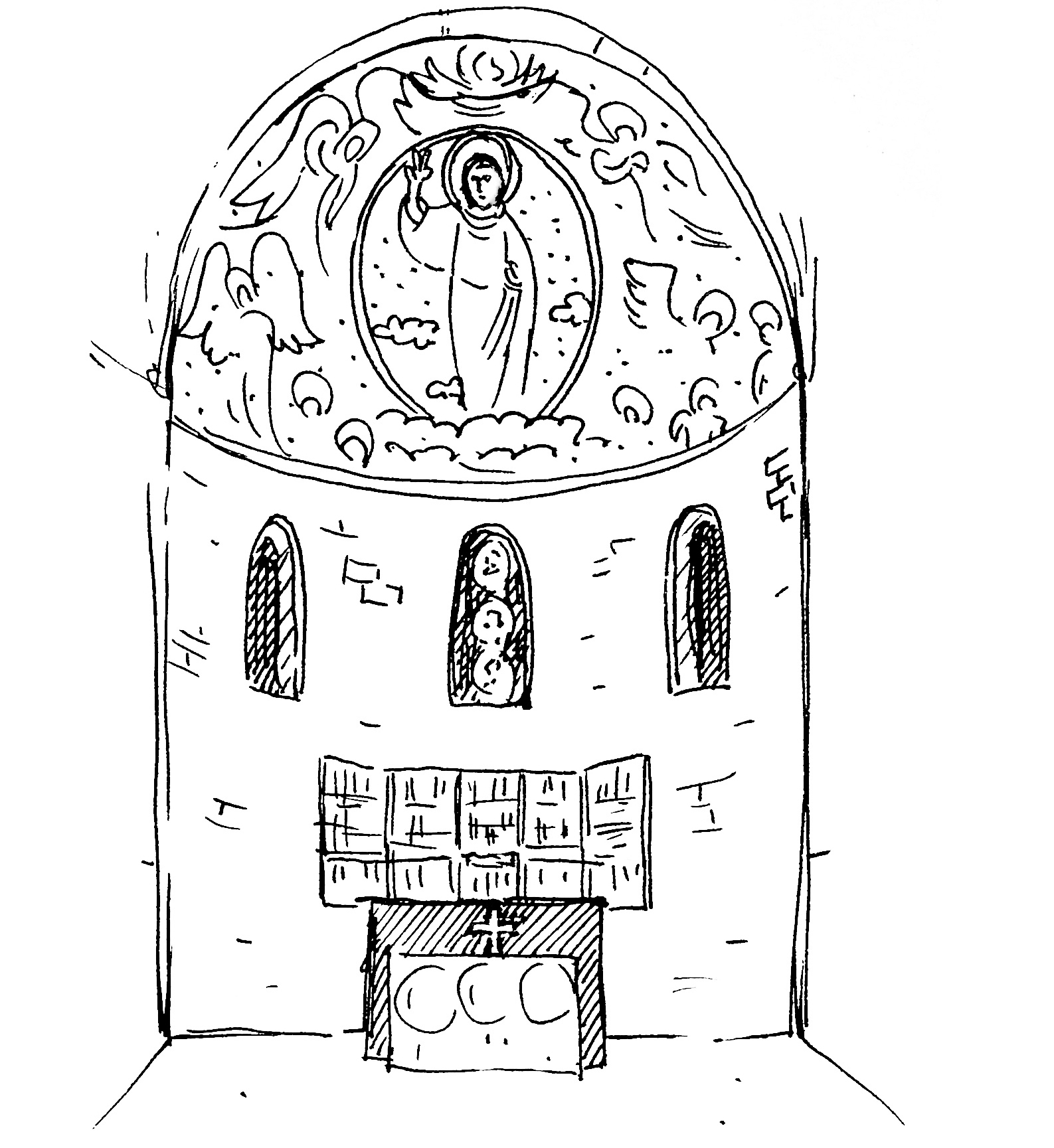

Inside the high apse dome is a gleaming glass mosaic.8The apse mosaic was made in the 1920s in a Byzantine or Eastern Orthodox style. When we approached from the nave, it looked like a golden eye watching over the Church. Now we can see the scenes pictured inside it. In the centre the Resurrection is in process. Jesus floats aloft among the clouds, rising noonward. His body is enveloped in a ‘mandorla’, an almond-shaped ring of light that signifies transcendence from earthly time and place. The mandorla’s upper tip touches the base of a blue sphere – presumably Heaven – from which the hand of God is reaching down. Beneath this central event, in the mosaic’s lower third, blessed mortals are being helped by angels to rise up heavenwards from their earthly tombs.

As a whole, the mosaic shows the second coming of Christ on the Last Day, at the end of time. It shows the moment of union between Heaven and Earth, says the Chaplain. In mystical terms, it ‘symbolises time breaking and becoming conjoined with the eternal.’

What’s more, the vertical plane the picture is set into is charged with its potential: the apse wall, she says, is ‘the thin membrane’ between this world of time and the realm beyond. We’re standing at the edge. And Heaven is on the other side.

The apse and altar. Drawing: Cathy Haynes.

Nothing ever happens

For a while in 2017–18 that was literally, materially true: an illuminated statement that read, ‘HEAVEN IS A PLACE WHERE NOTHING EVER HAPPENS’, stood in the public square, in the ordinary world, on the street side of the apse.

As the daylight faded the artwork’s glowing letters seemed to bloom in the soft blue air asking, What’s your idea of Heaven? What would it feel like to spend eternity in a place where nothing ever happens?

The sculpture is by Nathan Coley and its temporary installation there was the opening move in the Cathedral’s Råängen programme. Sjöstrand calls it ‘a fleeting poem’ that started a conversation within the community about eternity and what lies beyond this world.

For some the phrase ‘nothing ever happens’ seems negative, even sacrilegious, as if it’s saying ‘Heaven is boring’. Maybe that perception is instinctive if like me you’ve been raised on the promise of endless consumer novelty delivering a kind of Elysium on Earth. From that perspective, ‘nothing ever happens’ sounds like a claggy kind of stuckness, like the dreary prospect of a shopping centre Christmas on endless repeat. Perhaps, too, that fear of ‘ennui’ is more common for those of us sheltered from the distress of violent upheaval.9In a world where, to give a particularly miserable example, roughly one person in every 290 is now a refugee.

Yet the dream of Heaven is a dream of peace. Historically it’s imagined as a place of quiet joy, a sanctuary protected from the turmoil of the world: ‘Paradise’, for example, comes from the Persian words for ‘walled garden’. It’s also, critically, a place of completeness and perfection. In the heavenly state nothing happens because nothing needs to change. Its virtue is precisely that it’s a place without time.

In other ways of thinking, though, the divine eternal state is a ‘sanctuary made of time’, as the Jewish philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel described it. Eternity is time completely detached from material things. Rather than a place where nothing changes, it may be something more like a fleeting moment of bliss that lasts forever.

Is Heaven a place without time, or time without space? We don’t know, says Sjöstrand. The human mind can’t grasp the ineffable. Though we might get a glimpse of it:

There are situations where we can experience eternity in time, as if the border between time and eternity is porous. The quality of eternity can be, now and then, present in time. It may appear as a feeling of timelessness that comes over you in prayer or meditation, but also when you feel a strong connection with another person. Sometimes it might happen when you’re sitting on a train letting your mind drift – or when you’re doing the dishes or some other chore – and you feel exactly in that moment, not projected out into the past or future. It may come too when you’re concentrating and in flow, like when you’re dancing, and you feel part of something bigger.

And it might also happen, she suggests, through playing with the construction of time.

Nathan Coley, ‘Heaven Is A Place Where Nothing Ever Happens’, 2008. Installed adjacent to Lund Cathedral, 2017, part of the Råängen art and architecture programme. Photo: Peter Westrup.

Sunrise

‘What direction are you facing?’ asks the Chaplain. The apse points east,10That sundial- and compass-like aspect of its architecture may be most obvious to Muslims who come to the Cathedral to pray and visit, since in Islamic prayer practice it’s critically important to know the hour in solar (and lunar) time and the geographic direction of Mecca. These days Christian prayer isn’t timed as tightly by celestial events – though the Cathedral clock may have been an attempt to make it so. But the significance of the solar pattern to Christian thinking is profound – not least in how its temples are oriented, as we’re seeing here. and most of the time the whole building and its practices are organised to orient us that way too.11The apse actually points a little south of east and there are various theories as to why that is. I lean toward the explanation that, as well as being oriented to dawn as a daily event, it also aims specifically at one sunrise in the year, on the day dedicated to the patron saint of the Church when its foundations were laid nearly a millennium ago. The Chaplain emphasizes that, whatever the case, the main story here is Christ’s Resurrection: the Second Coming at dawn at the end of time is the focus of the Cathedral’s orientation, over and above any particular saint.

East is where the Sun rises and tomorrow starts. The building’s sacred alignment, then, is with the dawn rays that pierce the darkness, bringing clearer sight and a fresh start. East, Sjöstrand adds, is the location of the Resurrection: ‘Christ ascended to Heaven in the east in the morning and that is where, we hope, He will return.’

The primacy of east in the architecture here resonates with an ancient sensitivity to personal, bodily orientation in solar time-space. And the Chaplain encourages us to play with our own sense of it.

To stand and face the apse, she says, is to put yourself in ‘the great Easter direction’.12Easter is the Christian celebration of Christ’s Resurrection. By one theory, the word ‘Easter’ derives from ‘east’, the easterly direction. By another, it comes from the Spring celebration of ‘Ēostre’, the Germanic goddess of the ‘upspringing’ light of dawn. Either way, ‘Easter’ seems intrinsically linked to ‘east’. It’s a ‘way of playing with direction, geography and time’. And it can be a powerfully defiant and hopeful act:

With help from the Sun and the new-born light, we get inspiration to think about the possibility of being a new-born person. It’s a sign of hope, a sign of resistance, to sit or stand in the Church facing east with intention. It can help you bear times of great difficulty and darkness. It’s as if you’re saying, ‘I’m not giving up. I’m not going to just lie down. I’m standing here in my Easter position. I’m waiting for light to come. I’m waiting for a new life.’

Why does the relationship of our body to space matter so much?

Because as adults, we think we have to know everything in our head. But this stance is to let ourselves experience with our body – to put our body into the world – and just experience that.

To stand before the apse in the early morning can be a particularly moving experience, she suggests. This is when the three slender windows below the mosaic seem to glow of their own accord: their pictures come alive.

But on cloudy mornings and in the darker hours, the scenes are hard to pick out. There’s a debate going on at the Cathedral about whether the glass should be artificially lit. Should the window-pictures be made visible all the time?

‘The Cathedral is built in stone, but also in light,’ Sjöstrand reflects. Its substance is both material and immaterial, fixed and in flux, under human control and beyond it. Given that, she thinks, having to wait for the perfect moment to see the rays brighten the windows and clarify their picture is an important rite:

Now and then it’s good to have periods when things aren’t that clear – when you have to orient yourself in uncertainty to hope, to the possibility of being given a gift.

Going under ground

We head down under the apse to the crypt, the oldest part of the Cathedral.13Its east-facing altar dates from 1123. This is a more hushed, intimate space. It’s darker, too, so we have to move more slowly as our eyes adjust.

And I have a pressing question. We’ve seen how the Cathedral architecture seems shaped especially by two particular hours in the day, sunrise and noon: the resurrection of the solar orb and its highest peak. Given that light-oriented logic, is it possible to access the holy in an underground vault?

‘Yes’, says Sjöstrand, ‘You could say we imagine the crypt as a space for the meeting of Heaven and Earth, God and humankind.’

Across various traditions, the space below ground signifies nurture and rebirth. It’s the soil from which everything springs. It’s also the ‘night’, the place below the horizon where the Sun goes to rest and rejuvenate. It makes sense, then, that this is the place where the Cathedral community celebrates the ‘two great nights’ in the Christian tradition: Christmas and Easter, Christ’s birth and resurrection.

The crypt is deliberately a sheltering place, a sanctuary, Sjöstrand says. And she encourages us to sense a correspondence with it in our own being:

If we think about the Cathedral as a body, we are now in its heart, in its inner space. There’s a relationship going on I think – if you say yes to it – between your own heart and the inner space of the Cathedral. And as such it’s a reminder that you need such a space in your own life.

This ‘heart’ of the building also drives the body of the Cathedral community and its attitude to time. The Chaplain shows how by ending on a story. To tell it, she takes us over to one of the crypt’s medieval columns. The figure of a man has been carved into it with his torso buried inside, as if he’s part of the material structure.

There’s a famous old folk tale about this pillar, she says. And it goes like this.

Contemplating the carving of Finn in the Cathedral crypt. From Horace Marryat’s travel memoir, ‘One Year in Sweden; Including a Visit to the Isle of Götland (Vol. I)’. John Murray, London, 1862.

The fable of Finn

A monk called Lawrence was visiting Lund to spread the Gospels.14Lawrence the monk is thought to have visited Lund in the 11th century. He went on to become a saint. But he is not to be confused with the Lawrence we’ve already met, the 3rd-century patron saint of Lund Cathedral. At that time, there were no churches to preach from, only hills. Lawrence wanted to build a holy temple at Lund but couldn’t work out how to do it. One day he was beating his head over the difficulty when the ground began trembling and a giant thudded in.

‘Leave it to me!’, he boomed. ‘I’ll build your church.’

‘Oh?’, said Lawrence. ‘But how will I pay you back?’

‘I want the two great celestial orbs. Or, failing that, I want your two eyes.’

‘I can’t give you the Sun or the Moon, because they belong to God, who placed them there forever. But if you finish the Church, then you can have my eyes. That won’t stop me from preaching!’

He went off and came back with a mountain. He crushed it beneath his feet to make stones for building. He started with the crypt, constructing it like his own underground home. Then he laid the massive walls, which flew up as if by magic. After a short while he began making the roof.

As he worked, the giant laughed and sang to himself about how his baby son Sölve would get Lawrence’s eyes as a plaything tomorrow if the monk didn’t guess his name in time.

Poor Lawrence looked on with dismay. He tried guessing one name after another but, no matter how hard he tried, he was no closer to finding out the giant’s name. Now the building was nearly finished and Lawrence realised he would soon lose his eyes.

In great sadness he wandered alone into the countryside around Lund to take in its beauty for the last time. When he got as far as Helgonabacken he began to cry so despairingly from grief that his tears flew up to Heaven and came down as glistening snow.

Just then he was startled by a deep voice. It didn’t come from above, but from beneath his feet like the rumble of an earthquake. He stopped crying and listened. It was, he realised, the sound of a lullaby sung by a giant woman from her underground home.

‘Sleep, sleep, my little child,’ warbled Gerda, for that was her name. ‘Tomorrow your daddy Finn will bring your present home with him.’

The monk was delighted to have heard this and sprinted back to the Church shouting, ‘Finn! Finn! Put the last stone in! I don’t need you any more!’

The furious giant threw away the last stone and ran to the crypt to tear the Church down. He grabbed at a column and tried to wrench it away. But in his anger Finn forgot he couldn’t stand the Sun, which just then was rising in the east. A beam of light hit his eyes and he began slowly turning to stone.

Still to this day you can see the petrified Finn, frozen in time, stuck here in the crypt’s pillar.15A woman and child are carved into a nearby column in a similar style. Their presence is explained by versions of the legend in which Finn’s wife and child join him to wreck the Church. And maybe he got shrunk, too, because now he’s not so big.

But the story doesn’t end there. As he was being fossilized, with the last of his strength Finn screamed out, ‘This Church will never, ever be finished!’

The curse came true. Lund Cathedral has never been completed in all this time. Still today it has missing bits and always something that needs repairing or redoing.

The best curse of all

There are various versions of this tale, ancient and modern – and maybe every telling gives it a new detail or twist. In one old transcription, for example, Lawrence’s deadline is sunset and sunrise isn’t mentioned. In another, there’s no play on the correspondence between heavenly orbs and human eyes – between celestial and earthly forms, the eternal and the transitory, the macrocosm and the microcosm. But this is the one Sjöstrand tells on our walk, and she closes it with these words:

Of course Finn thought that was the best curse of all. But for us it was a blessing.

It is true this Church is never finished, with its endless repairs.

But it’s also true in a broader philosophical way.

On Earth, nothing is ever finished – we’re in a constant state of becoming. And each generation has something new to bring.

Ingeniously, then, the current Lund Cathedral community is recasting Finn’s old jinx as the gift of unending creativity and regeneration. Sjöstrand explains how that idea is being developed:

Through our Råängen programme we’re creating a dialogue between the time the Church comes from, the time we’re in and the generations to come. That is, between a thousand years of the past and a thousand years of the future. We are mid-way through the journey.

On the one hand the playful reframing of its origin story is helping the Cathedral articulate and develop its responsibility to past and future generations. It’s using its own great age and history as a way of looking far beyond the short term – like an ark trying to carry the deep past and the far future within it, without abandoning either to a distant shore.

On the other, its theological traditions offer different ways from the mainstream of thinking about, performing and sensing time, as we’ve started to investigate here. Time, like the Chaplain says, is a construction that can be played with.

Through the Råängen project, the Cathedral is inviting collaboration with artists, thinkers, writers, archaeologists, architects and historians to do just that. Råängen began very recently. It’s now in full flush with the launch of a specially commissioned new work by Nathan Coley, ‘And We Are Everywhere’, installed on church land outside Lund, in June 2018. The work seeks to address urgent global issues such as homelessness, migration and the role of faith in 21st century life. And aptly enough, this architectural expression of compassion and hope is oriented east, slightly out of kilter with the local building grid, in the direction of sunrise.

Completing the circle

Now we’ve come to the end of our tour. Before we turn without thought to walk back west through the Church, Sjöstrand invites us to pause and consciously reorient ourselves once more:

Try to put yourself in the direction of returning to the world of time – to ordinary time. You might reflect, ‘I’ve filled something in myself in this ritual time, this other time’. Bring that with you, but step into time again.

-ends-